|

Yehuda Ashkelon is there, at his side, watching him. During their time in the labor camp, this youngster gave Pinchas a leg up, thus helping him to escape. Pinchas glances at his friend and says to him softly, “Yehuda, I’ve done my duty.” On that, he leaves, with his meager bundle, leaving behind the Nilasz uniform. Exiting the building, he crosses the courtyard, goes through the gate and comes into the street, without a backward glance. He moves off towards an uncertain future. He is not yet 22, but misfortune has already scarred him deeply.

Walking down the street, thoughts jostle each other in his head, names, dates, places and landscapes that have just been written in history in letters of fire. Many faces loom up, those of the many friends who did not manage to live till this much wished for day, and especially of his parents, his bothers and sisters, who disappeared in the turmoil, in the smoke of the crematoria, not leaving him even a grave at which to cry. These dreadful images mix with memories of a happy childhood, his time in yeshiva, discovering the “Bnei Akiva” youth movement, the talmudic training he received from his father in Kleinwardein, the very active time in Budapest. Then everything collapsed, forced labor in the camp, the audacious escape, his dangerous activities under cover of his Arrow Cross uniform, the fight against the clock to beat the Angel of Death, the impossible missions, the Danube red with Jewish blood and the two shots from his own weapon one dark night, which left the bodies of two real Nilasz lying in the street. He remembers everything. And today the long-awaited liberation.

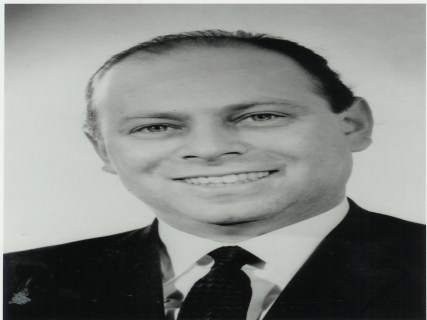

That’s a thumbnail sketch of Pinchas Rosenbaum’s story, the man who endangered his life for months on end and managed to save hundreds of Jews, individuals and families, during the darkest days of the Second World War in Hungary.

Pinchas Rosenbaum was born on 2 November 1923 (23 Cheshvan 5684) in Kleinwardein, Hungary, the progeny of a long line of rabbis. His forebears were disciples of the Chatam Sofer and direct descendants of the Maharal of Prague. Among them could be counted eminent scholars, spiritual guides and community leaders, commentators on the Torah, and authors of works on Halachah and Aggadah. His grandfather, the author of Lechem Rav on the siddur, the Jewish Prayer Book, was the rabbi of Kleinwardein. At his death, Pinchas’s father, Rav Shmuel Shmelke Halevi, succeeded him in the post. Rav Shmuel Shmelke, the last rabbi of Kleinwardein before the Shoah, was deported together with his family and community to Auschwitz. Pinchas was the only one of this illustrious family to escape.

A remarkable Torah scholar in his own right, Pinchas had been ordained for the Rabbinate at the age of 18 by leading Hungarian rabbis. During his time studying in yeshiva he joined the “Bnei Akiva” youth movement, and enthusiastically adopted the Zionist principles of “Torah and work”. Within a very short time he had become one of the national leaders of “Bnei Akiva” in Hungary.

During the Nazi occupation, Pinchas was involved body and soul in the organization of Jewish youth who mounted rescue and escape missions to snatch Jews from the Nazis’ grasp. Together with his companions he managed to save hundreds of his coreligionists, sometimes complete families, finding them shelter and providing for their needs.

Pinchas risked his life 24 hours a day. Hiding behind noms de guerre and thanks to his Aryan appearance, he succeeded in fooling the Hungarian Nazi authorities and sometimes even his fellow Jews. More than once, learning that a family was about to be taken, he would burst in himself, wearing the dreaded uniform of the Nilasz and chase them out of their apartments with shouts and curses, the unfortunates being pushed and shoved with threats into the black cars of the Arrow Cross. That was so that the non-Jewish neighbors thought these Jews had been taken by the Nazis. He brought them to the “Glass House”, the famous shelter on Vadatz Street, where thousands of Jews lived on false certificates. Pinchas was also involved in producing these documents. It was not until he had brought them safe and sound to the “Glass House” that Pinchas at last revealed himself, apologizing to his brethren for having terrorized them, explaining, “It was the only way to save you.” These men, women and children, who had just escaped a real round-up, clearly understood his behavior and thanked him effusively, realizing the danger had put himself in. If he was caught, there could be no doubt that he would get a bullet in the head straight away.

His actions became increasingly audacious, beggaring the imagination. One evening, coming down from the attic of the “Glass House”, he was went up to his friend Avigdor Friedman, known as Viki, and said to him, “Viki, you are going to have lend me your suit for this evening.” “My suit?” exclaimed Viki. “Yes”, explained Pinchas. “Tonight there is a party at the Hungarian police and I must make a good impression there. I can’t go in military uniform. If I am not uncovered, I’ll give you back your suit of course. If they take me, well, then you’ll have lost your suit…” Faced with Pinchas’s black humor, Viki could not repress a bitter smile. Without asking any questions he tool off his good suit, the only one he still had, and gave it to his friend. “Good luck”, muttered Viki. “With G-d’s help”, replied Pinchas as usual. Without ado he put on the suit, arranged his appearance and left the “Glass House” for his secret destination. The next morning he was back, pale and exhausted. Viki rushed up to him. “Thank G-d, there you are. But why are you so pale, what did they do to you?” Pinchas eased himself heavily into a chair and replied, “Listen, I spent the night drinking with them, I had no choice. While they were drinking, one of them let slip the name of the Jewish family they were preparing to round up in the early hours of the morning. I waited till they were completely tipsy so that I could slip out. I ran to the address they had mentioned and managed to warn the family. Now I’m tired, I must sleep, good night. Oh yes, I forgot, your suit is still in one piece, I’ll give it back when I wake up.” With those words he sunk into a deep sleep.

In November 1944 the underground resistance and rescue organization found itself in great danger. Zvi (Zeidi) Zeidenfeld had been arrested by the Gestapo. Zeidi, whose assumed name was Kovacs, had International Red Cross certificates on him, hundreds of blanks ready to be forged. The Nazis intended to interrogate him to extract the names of the other members of the resistance and find out the source of the documents. Zeidi refused to speak and he was horribly tortured, but the Gestapo endeavored nonetheless to keep him alive. Zeidi survived the first round of interrogations without revealing what he knew. Before starting the second round, the Nazis gave him a few days respite. When his comrades from the “Glass House” learnt of his arrest, he was already in hospital, his body broken by torture. It was a makeshift hospital at 44, Vessleny Street. The place had once served as a Jewish elementary school that had been requisitioned by the authorities. During a meeting that ran into the small hours of the morning at the “Glass House”, it was decided to get into the hospital to get Zeidi out. The group had never undertaken such a risky operation. Several young members of various Zionist organizations volunteered. After careful thought, the choice fell on Pinchas and Yossi, a young member of “Hashomer Hatza’ir”. They went out into the cold, rainy night at three in the morning. Under their SS uniforms and long leather coats that covered them, they carried loaded submachine guns. In front of the hospital was a guard, who it turned out was a Jew in convalescence. “Gestapo,” they told him. “Take us straight to the Jewish prisoner, room 243 on the second floor. We have some accounts to settle with him.” “I’m not allowed to let anyone leave. I’m just the night watchman, I have to pass on your request to my superiors,” replied the terrified guard. Pinchas looked him straight in the eyes and asked brusquely, “Are you a Jew?” “Yes”, muttered the other, terrified that the two Nazis would kill him on the spot. “We too, we are also Jews”, whispered Pinchas in a Yiddish that left no doubt as to their identity. “We have come to get a comrade out of here, otherwise the Gestapo will kill him. You have to help us.” “But if I let him into your hands, I’m the one they’ll kill.” “Don’t worry,” Pinchas reassured him, we’ll take you with us, to a safe place where you won’t need to worry any more. Go get our patient now.” The guard disappeared into the interior of the hospital, leaving Pinchas and Yossi at the entrance. A few minutes later two SS men could be seen dragging a half-conscious patient, with another man who was holding a small black leather bag scurrying behind them. Anyone in the street at that hour was not surprised. This type of thing happened often, the SS going into the hospital, emerging with a wounded or sick person, who was never seen alive again. The little group moved rapidly in the direction of the “Glass House”, where they arrived around 4.30 in the morning. The gate swung open and Zeidi was taken in hand straightaway by the medical team. He and the documents he had were saved.

If we wanted to relate all the courageous actions that Pinchas Rosenbaum took part in, it would require a thick volume. Pinchas himself never made much of it. Occasionally, on his travels around the world, he would meet a man or woman who owed him their life, and when such a person started telling about what he had done, his heroism and courage, Pinchas listened intently, as though they were talking about someone else…

At the end of the war Pinchas Rosenbaum married Stephanie Stern and settled in Geneva, where he worked in banking. They had three children, two sons and a daughter, and all three live today in Israel. Alongside his finance activities, he was a dynamic, militant Zionist, working with all his strength for the State of Israel, even carrying out a few missions for the Mossad and for Israeli security. He died on 23 October 1980 (13 Cheshvan 5741), when he was only 57, and was buried in the Har Hamenuchot cemetery in Jerusalem.

His memory survives through his acts of courage, but especially through the hundreds and thousands of sons and daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren brought into the world by Jews saved by his audacity and tenacity, and who without him would never have seen the light of day.

* Menachem Michelson is a journalist on the Israeli daily newspaper, Yedioth Aharonoth. He is currently writing a major biography of Pinchas Tibor Rosenbaum zl, which will soon be published in Hebrew and English.